Beyond Covid: A shift from treatment to prevention is enabling animal health to move to One Medecine

This article is based on a presentation made by Dr. Michael Hemprich, Ceva’s Director of Business Development & Strategy, at the 7th annual Animal Health, Nutrition and Technology Innovation Europe event. The theme for this event was Shaping the Future of the Animal Health Industry by Showcasing Innovations in Prediction, Prevention and Cure. It was held in London, February 21 – 23, 2022, a short walk from the site of the original Globe Theatre where many of Shakespeare’s plays were first performed.

What’s Shakespeare got to do with animal or preventative health?

Most of Shakespeare’s life (1564-1616) was impacted either directly from a health perspective or economically by bubonic plague. Indeed, in the 4 years between 1606 and 1610, London theaters were only open for a total of about 9 months as lockdowns ravaged the London economy.

Of course, London’s theatres, in common with those all around the world, went dark once again during the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021; many, it is feared, will never open again.

We now know that the plague that ravaged London in the early 17th century was a serious, infectious disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and spread by flea bites: flea species that lived on rats switched to humans when infected rat populations died out. But during Shakespeare’s time, no-one understood that it was the rats they were living with that were spreading the plague.

What will a One Medicine health system post-covid look like?

Many issues have emerged post-covid with people calling for regeneration to heal a broken planet and fix, for example, our environment and food systems. And yet, health systems and the people that work in them always seem untouchable for public scrutiny, largely because of the profound (and earned) respect the public has for our doctors, nurses and health staff that treat us when we are sick.

Maybe, because I’m a trained veterinarian, I’ve been convinced for many years that seeing our own health in isolation is a mistake. We need to move to a One Health approach, recognising that the health of people, animals and our environment are fully interlocked. Despite more calls recently for such a move, in reality the movement has so far been a form of ‘shotgun wedding’ with many human health practitioners seeing no real need to come to the altar.

Yet, with 3 in 4 emerging human infectious diseases coming from animals (and 72% of them from wildlife), it’s pretty obvious that to better protect ourselves, we need to treat the cause at source, in the forests of the Congo or Vietnam, not in the hospital beds of London, by when it is often much too late.

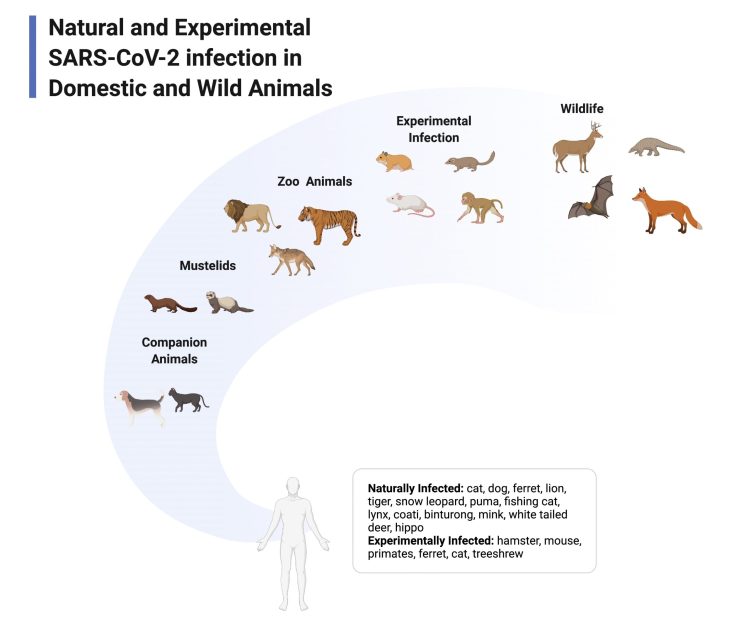

As of February 2022, the SAR-CoV-2 virus that causes Covid-19 has been confirmed to infect more than a dozen species including pets, zoo animals and free-living wild animals. However, it is likely that infections are more widespread as relatively few species have been tested. If the coronavirus is living and spreading among animals and occasionally jumping back to humans, this process poses threats to public health: the animals can act as a reservoir of infection, even as the number of human infections reduce and, as the virus adapts to the unique characteristics of different species by mutating, new variants can arise that could infect people.

We need a tectonic shift in our thinking and towards health and realise that we are only a small part of a holistic ecosystem, where we share a pool of diseases with other species, including wild animals – diseases which pass between us and them.

This is not new: the early One Health and vaccination pioneers understood this well, but there is now almost a sense of shame to recognise this in the minds of some scientists.

The modern One Health pioneers were pluri-disciplinary:

Edward Jenner (1749-1823), who was never formally trained as a doctor or veterinarian (as he practiced almost a century before comparative medicine was formally recognised), was the first to demonstrate that exposure to the zoonotic cowpox lesion helped protect against human smallpox – arguably the most important observation in the history of infectious disease.

The concept of vaccination was developed further by Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) and he came up with the term vaccination: vacca coming from the Latin for cow, was a tribute by Pasteur to Jenner. Now, the word vaccination is familiar to billions worldwide.

Pasteur’s contribution to medicine is impossible to define in terms of a particular discipline, as he was a chemist, biochemist and biologist, amongst others.

The graphic produced for the brochure for the 7th annual Animal Health, Nutrition and Technology Innovation Europe event indicates how the coming together of several streams of medicine – Prediction/Prevention/Treatment – are once again creating the type of pluri-disciplinary approach that will be necessary to prevent future pandemics

Through the Covid-19 pandemic we’ve seen endless data, modelling and the fastest roll out of new technology vaccines ever witnessed as governments have struggled to control the disease.

We’ve also seen the creation of specific One Health bodies, such as here in the UK with the creation of the UK International Coronavirus Network (UK-ICN), which will increase integration of human-veterinary coronaviruses research and innovation.

Let’s not forget that at Ceva we’ve been dealing with another coronavirus, infectious bronchitis (IB) in chickens, for over 30 years now and so have developed interesting knowledge about how to create and use vaccines in the most effective way.

“No one is safe until we are all safe”

The phrase “no-one is safe until we are all safe” has been used many times recently to remind us that as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) continues to circulate unchecked anywhere in the world, the opportunity for new variants to arise is still present. But what about the animals and the bats that were probably at the origin of this pandemic? How do we vaccinate bats deep in their caves?

Trying to stamp out such a globally dominant disease one country or outbreak at a time does not work. It’s like playing ‘whack a mole’.

Prevention better than cure – and more cost effective

A recent paper [1]published in the respected journal Science Advances estimated the cost of implementing effective primary pandemic prevention, which would entail better surveillance of pathogen spillover and development of global databases of virus genomics and serology, better management of wildlife trade, and substantial reduction of deforestation. These measures were designed to address the fact that ‘Humans have extensive contact with wildlife known to harbor vast numbers of viruses, many of which have not yet spilled into humans’, and, the authors suggested, represent an improvement to the current approach to pandemics, which boiled down to taking action only after people get sick. They found that the cost of these preventive actions, estimated at USD 20 billion a year, was small in comparison to the estimated value of lives lost to emerging viral zoonoses, conservatively estimated at USD 350 billion a year, and an additional USD 212 billion in direct economic losses. The paper points out these preventive approach also came with substantial co-benefits, including helping to avoid carbon dioxide emissions, conserving water supplies, protecting indigenous peoples’ rights and conserving biodiversity.

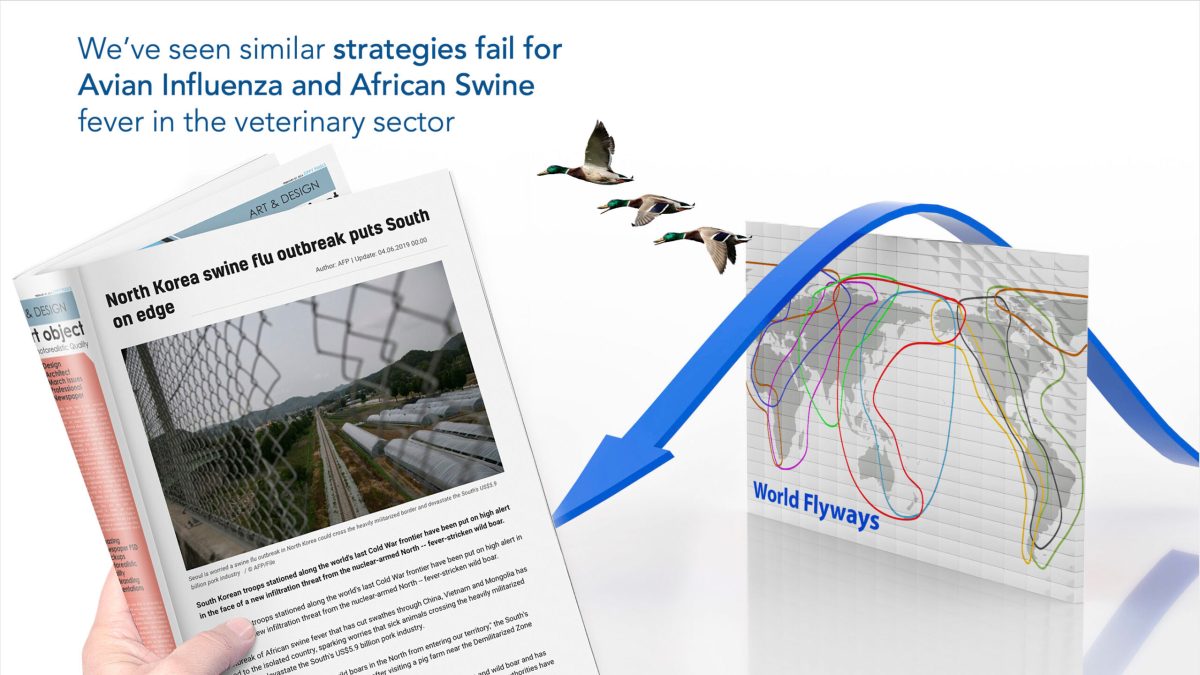

We’ve seen similar reactive rather than preventive strategies fail for avian influenza and African swine fever in the veterinary sector; ultimately no frontiers, walls or fences can stop their spread.

Take for example human flu control in Europe. Many scientists advise that people should be vaccinated, even with a vaccine that is 60-70% efficacious, and that is great advice. But we also know, through our work with the International Swine Flu Network, that flu strains are also endemic in pigs, including pandemic strains that can spill over from swine to people, which they do, all year round. So, to stop clinical disease and prevent the rise of potentially disastrous new variants in order to stop the next pandemic, we should be calling for the vaccination of pigs as well. But who is doing that?

It’s not a question of efficacy, as was erroneously suggested in an otherwise excellent article[2] in the Scientist looking at the origins of the swine flu pandemic in 2009. The real problem with flu vaccines for pigs isn’t the fast pace of evolving strains, as the authors suggest, but the reluctance of vets and farmers to implement and invest in the recommended vaccination scheme. This requires two initial doses for both sows and their offspring followed by booster vaccination every 4 months for sows. Many vets and farmers regard this as being too costly and time consuming – but if it’s going to help prevent the next flu pandemic in Europe, shouldn’t EU states be considering sharing some of the costs?

Aside from the question of money, a shift to prevention first, with reinforcement of surveillance and emergency preparedness, is therefore essential.

Fortunately, recently there are some positive moves in this direction. For example:

A the global level, on 30 March 2021, leaders from all around the world joined the President of the European Council, Charles Michel and the Director-General of the World Health Organization, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in an open call for an international treaty on pandemics[1], drawing from the lessons learnt during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a joint call for the treaty they stated:

“There will be other pandemics and other major health emergencies. The question is not if, but when. Together, we must be better prepared to predict, prevent, detect, assess and effectively respond to pandemics in a highly coordinated fashion. To that end, we believe that nations should work together towards a new international treaty for pandemic preparedness and response.”

Also, the French government is promoting the creation and adoption of PREZODE (Preventing Zoonotic Disease Emergence) at the G7 summit being held in June 2022. This is an innovative international initiative to understand the risks of emerging zoonotic diseases, to develop and implement innovative methods to improve prevention, early detection and resilience in order to ensure rapid response to the risks of emerging infectious diseases of animal origin. We at Ceva are very happy to partner with CIRAD and other public sector actors, to play our part in this important programme.

As part of our new business purpose initiative, we will also create the Ceva Foundation that will focus specifically on understanding how we can better prevent diseases in wildlife, the major reservoir of emerging infectious diseases, to improve their health (and chances of survival) and help better protect our own.

Ceva – committed to preventive approaches

Ceva’s Chairman & CEO Marc Prikazsky, who like many other managers at Ceva is a trained veterinarian, likened the company to a fire brigade in his analogy made more than 10 years ago in the paper “World Health at Stake, Who Cares, Who Pays?” :

It’s like being a fire brigade. If they are called early enough, then they can rush and put the fire out before too much damage is done. That is the emergency response mode. For emergency response to be effective, you need proper monitoring and information systems, 011(or similar) emergency call numbers, quick access to fire hydrants nearby, and the right equipment. The less these elements are in place, the longer it takes to put out the fire, and the more damage it will do. In this analogy we would consider ourselves the makers of some of the firefighting equipment: we know what sort of techniques, materials and pumping systems will put out what kind of fire. Currently we are usually asked to provide these while a fire is in full blaze. But there could be another mode – prevention. Ceva’s knowledge about fires could be better engaged in preventing fires from breaking out – contributing our knowledge towards influencing the building codes, prohibiting risky behavior, isolating potential sources of fire, stocking hydrants, creating evacuation plans, and more.

Ceva management believes firmly that prevention-mode and emergency-response facilitation could and should still be improved – especially when considering this in terms of costs that could be reduced or prevented by tackling animal diseases before they cause widespread damage. With better prevention and better emergency response, the global health system would be spending only a fraction of the cost of what the economic damages of these uncontained diseases are today.”

Covid-19 has demonstrated that many future generations will continue to pay, will we now have the courage to learn the lessons and change our approach to health.? Shakespeare’s generation wasn’t aware what was causing the fires, we are, even if we don’t know exactly where the next one will flare up, there is no more excuse not to be prepared.

Discover our Economic and Social Report 2022 here.

[1] https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abl4183

[2] https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/the-long-journey-to-resolve-the-origins-of-a-previous-pandemic-69141

[3] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/coronavirus/pandemic-treaty/