The Covid-19 pandemic reminds us that we share the same “disease pool” with both wild and domesticated animals and the better we protect them, the better we protect ourselves. For perhaps the first time in the long history of “plagues”, we understand what we are facing and know that vaccination will be a key part of “normal health” and living being fully restored.

Thanks to its ambitious and extensive research programs Ceva has become a world leader in veterinary vaccines with almost 50% of its sales coming from this sector. As a result, the company now offers livestock farmers, and the veterinarians who support them, a very comprehensive range of innovative and effective vaccines that provide protection against many major infectious diseases. In most cases, these mass-produced, registered, standard products are effective on farms throughout the world, helping to ensure that billions of animals remain healthy.

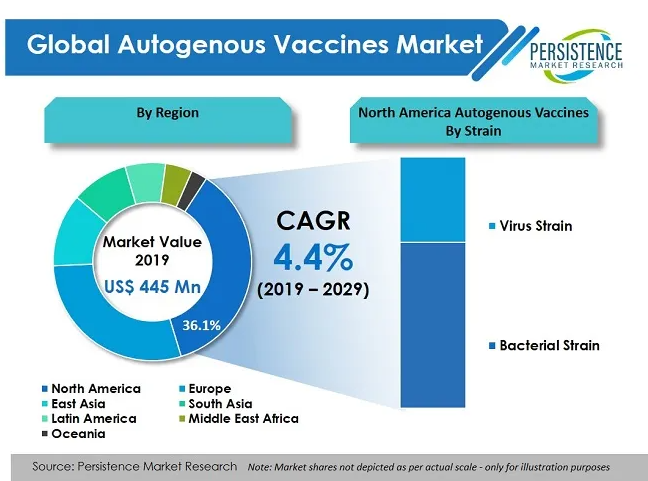

Sometimes, however, a specific solution is needed in cases where a new strain of disease-causing bacteria or virus emerges or for a disease that is not covered by one of the registered and commercially-available products. To meet this need, over the past few years Ceva has emerged as a global leader in the rapidly growing field of custom-made vaccines, also known as autogenous or auto-vaccines.

This is not however a new field, the very first known vaccines were developed in a similar way in 1796, when an English doctor, Edward Jenner after finding a case of cowpox in a dairy maid collected matter from her pustules and inoculated an 8 year old boy. After a number of similar studies, he was able to convince a rather skeptical medical community of the value of his breakthrough and the concept of “vaccination” (which he named from Variolae vaccinae – “smallpox of the cow”) was born.

Later, in the 1870s and 80s in France, Louis Pasteur developed the first vaccines for anthrax and rabies. French-born Pasteur’s contributions to public health, science and society were immense. He was a chemist, biochemist and biologist amongst other disciplines. His achievements included helping the Impressionist painters prepare better paint colours, to applying the concept of fermentation to the beer and wine industries and leading to the concept of milk pasteurisation. He is also credited with providing direct support for the germ theory of disease and its application in clinical medicine.

What are Autogenous Vaccines ?

Autogenous vaccines are made specifically for a designated herd or flock on a particular farm. Having first determined that the disease present on the farm cannot be prevented using existing licenced and commercially available products, the farm’s veterinarian obtains a sample from a sick or dead animal. The disease-causing microorganisms are cultured and characterised in the laboratory and the isolated pathogens then transformed by the vaccine manufacturer into custom vaccines. This process usually takes 4-6 weeks, after which the autogenous vaccines can be used on the farm, under veterinary supervision, to alleviate the original disease problem.

Ceva first began producing autogenous vaccines in the USA and later in 2016 acquired Biovac, a leading manufacturer of autogenous vaccines, allergy treatments and associated reagents in France.

Bespoke Solution

Ceva’s autogenous vaccines expertise, which encompasses veterinary medicine, microbiology and vaccine production, can be used to produce custom vaccines for a wide range of animals. This includes minor farmed species, for which off-the-shelf vaccines are not available, and also companion animals. The company’s autogenous vaccines have been produced to provide bespoke protection for pigs, poultry, horses, rabbits, fish and even wild animals.

In a notable first, over recent years Ceva has worked with a number of partners to produce a custom vaccine to protect one of the world’s most endangered species the Amsterdam island albatross with only 51 remaining nesting pairs. A poultry disease, avian cholera, introduced to the remote Indian Ocean island, was causing high mortality rates in albatross chicks but trials of the Ceva Biovac autogenous vaccine (initially on the more common Indian Yellow-nosed albatross), have demonstrated much-improved survival rates in vaccinated chicks, giving new hope for the species.

More than “filling the gap”

Autogenous vaccines play a much more important role than simply “filling the gap” where there are no commercial products currently available. They play a vital role in preventative health management programmes, allowing veterinarians to stay close to the farm, better understand the existing disease status and as a result reduce the need for emergency treatments. This is particularly vital to ensure that antibiotics remain effective and available for use when they are needed to safeguard the lives of people and animals. Autogenous vaccines can also be used to fight against multi-drug resistant bacteria. Finally, they can help support public health programs, for example by helping to control food-borne pathogens such as Salmonella and Escherichia coli by preventing these infections in poultry and pigs.

Demand for autogenous vaccines has been growing so fast that it became clear that the Ceva Biovac facility in France was no longer big enough to cope with this. A second, much larger facility was therefore built on the existing site during 2019-20. The global coronavirus pandemic has delayed the final official inspections needed before the new facility can start production but with the easing of lockdown restrictions, it is hoped that it can come on stream in September 2020. This new capacity will mean that Ceva can produce custom vaccines to complement its mainstream products, providing even more customers with a more complete set of tools to maintain the health, productivity and welfare of their animals and to help safeguard public health.